I have long been intrigued by the principles that guide the proper organization of software code into modules (aka packages, namespaces). Ideally, these principles should be well-defined, leading to the same modular structure whenever the same software requirements are given, much like in mathematics. While I have come across various hints and best practices, I have yet to find a comprehensive and convincing framework for this, therefore, I decided to explore and define these principles myself. In the following sections, I outline my ideas, and I hope you find them useful.

In my research, I found the following books to be particularly useful:

- Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides is an inspiring and practical book

- Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software by Eric Evans is inspiring and important for my conclusion

- Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture by Martin Fowler has many useful sections even though some are outdated

- Microservices Patterns by Chris Richardson is an inspiring and practical book

1. Problem

Modules (aka, packages, namespaces) and classes (or their equivalents) are the fundamental building blocks of an OOP based application. In complex software projects, deciding which classes to create and how to organize them into modules can be challenging. Design Patterns and SOLID principles help significantly with class structure but are less useful for organizing modules. Additionally, to do both effectively, it’s crucial to maintain a clear focus, one that resists the influence of frameworks or technical constraints, to prevent structuring the software incorrectly.

2. Layers and Modules

From the start, the most promising approach was to map an application’s layers into modules. In this context, along with the books mentioned earlier, I also recommend these excellent articles:

1. https://alistair.cockburn.us/hexagonal-architecture/

2. https://blog.cleancoder.com/uncle-bob/2012/08/13/the-clean-architecture.html

3. https://jeffreypalermo.com/2008/07/the-onion-architecture-part-1/

After reading at least these articles, it becomes clear that translating layers into modules is not straightforward. This is because a module structure resembles a tree (like a file system), whereas layers are more like horizontal lanes or concentric circles. Another challenge lies in the layers themselves: which ones should be used? In the following sections, I attempt to identify them through a logical and systematic approach.

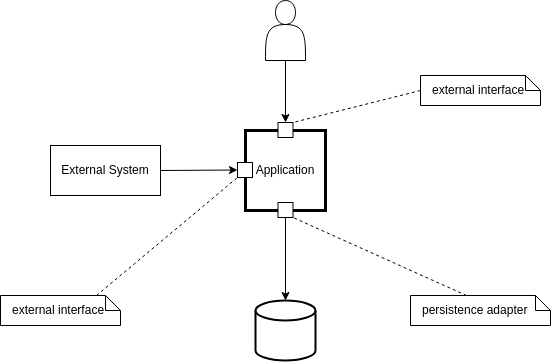

3. The Boundary

One obvious observation is that every application (e.g., desktop, microservice, etc.) has a boundary. In this context, I find Hexagonal Architecture particularly useful. This boundary consists of all the application’s external interfaces, along with the adapters that enable it to interact with the external services it depends on.

Example of external interface implementations:

- RESTful endpoint handlers

- queue message listeners

- WebSocket message listeners

- command line reader

Everything that requests something from an application does so through an external interface.

Example of adapters:

- DAO (i.e. Data Access Object, SQL or NoSQL based, implements the CRUD operations)

- Lucene index reader & writer (a kind of a NoSQL database)

- (message) stream reader & writer (e.g. Kafka topic pull-reader & publisher)

- file system reader & writer

- command line reader & writer

- WebSocket message publisher

- RESTful client

When an application needs to request something, it does so through an adapter that connects it to the corresponding external interface.

In Hexagonal Architecture, external interfaces are often referred to as (primary) adapters. However, I prefer the term external interface because it better conveys that the application is exposing or offering something to an external system. In contrast, the term adapter suggests something the application uses to access an external system. This is the meaning I will use moving forward.

The application’s boundary corresponds to the Interface Adapters ring in Clean Architecture. However, what I refer to as an external interface is unrelated to the External Interfaces segment in the Frameworks and Drivers layer of Clean Architecture. While I have some assumptions about what that segment represents, the author does not elaborate on it in his article, so I will not either.

The term external interface is meant to convey the idea of an application interface for the outside world. An alternative term could be remote interface, but external interface seems more appropriate, as even a process-to-process interface qualifies as an external interface, despite not being a remote one (i.e., one that allows access from a remote machine).

In Onion Architecture, the application’s boundary corresponds to the outermost ring.

But why is the boundary necessary in the first place?

Because the remaining part of the application, let’s call it the body, uses a “language” the application clients (e.g. systems, user agents) don’t know. The boundary‘s role is to “translate” the external requests into the body “language”; the body doesn’t care about the “languages” the boundary understands, its job is to handle the requests no matter their source or journey to the body.

For example, some external systems might use a queue to access the application features, in which case the external interface implementation will be a message listener, while others might use a RESTful endpoint, in which case the external interface implementation will be a RESTful handler. The external interface implementations will “talk” differently with the external systems but in the same way with the body.

The difference between the boundary and the body might be incredibly blurry when using a framework or some particular technology. For example, a framework could directly use the body based only on Java-annotations/.NET-attributes, hence one could legitimately wonder where the external interface and its implementation are; well, they are still there though completely covered by the framework. Change the application to provide e.g. an additional communication channel to the same body feature, one the framework doesn’t support, and the external interface will become visible.

4. The Boundary Modules

Let’s determine the “rule” for module creation based on the examples below.

4.1. Examples

a. Application exposing RESTful endpoints and persisting to a database

In this situation, I like to have in the application root these modules (directories):

- datasource (e.g. SQL/NoSQL DAO classes)

- rest (RESTful handlers and clients) – if crowded, I might split its content into in (for handlers) and out (for clients) modules

b. Application exposing RESTful endpoints, persisting to a database and using a messaging system (e.g. Rabbit MQ)

In this situation, I like to have in the application root these modules (directories):

- datasource

- queue (message listeners and producers) – I might split its content into in (for listeners) and out (for producers) modules

- rest (RESTful handlers and clients)

c. A complex application providing a lot of external interfaces and using a lot of adapters

In this situation, I like to have in the application root this structure:

- datasource

- cache (in-memory database used for caching but not distributed locking)

- dao (DAO classes for Sql or NoSql databases)

- index (Lucene index reader & writer)

- fs (file system, e.g. for loading/writing data from/to CSV, XML, etc)

- adapter (or io or infrastructure)

- mem (in-memory database used for other than caching, e.g. for distributed locking)

- queue (message listeners and producers)

- rest (RESTful handlers and clients)

- shell (command line reader & writer)

- stream (Kafka topic consumer & publisher)

- websocket (message listeners & publishers)

- mvc (for MVC controllers)

- scheduler (this behaves like an external interface periodically invoking the application features)

d. UI Applications

UI applications use fewer external interface types than a backend application, usually RESTful and WebSocket. Modules structure:

- rest

- websocket

If there are many rest/websocket submodules, I group them by their target, e.g. the (micro) service they belong to.

4.2. Conclusion

One can see I prefer keeping the datasource module in the application root; it’s because usually there’s a lot of activity there otherwise I’d move it into the adapter module. For me, the “rule” is:

keep the most crowded external interface & adapter modules (EI&A) in the application root while everything else into the adapter module. For example keep only datasource and 2 other critical EI&A modules in the root while move the rest to the adapter module.

Additional module structuring hints:

- use in (for external interfaces) and out (for adapters) modules inside adapter sub-modules

- use consumer and producer (instead of in/out) inside queue

- use listener and client (instead of in/out) inside rest and websocket

- if not crowded, use the event module for websocket, stream and queue

- name the modules closer to the technology, e.g. topic instead of stream for Kafka

5. The Boundary Model

Messages (e.g., diamond, square figures) are exchanged between the exterior and the application body; they are DTO (Data Transfer Objects) coupled to a particular technology/communication channel type, hence usually incompatible with the body’s “vocabulary”. The boundary must “translate” the in-DTO (i.e., received ones) to the body “language” because the body is oblivious to the external systems. These DTO are parameters or results (i.e., out-DTO) of the boundary class methods; it is desirable for them to stay next to the class using them. If used by many classes (e.g. the queue and rest classes), they should be placed into a new adapter sub-module, named dto or model.

To communicate with the body, the boundary needs converters/factories to “translate” the in-DTO to body objects and the body objects to out-DTO. I always like to put the factory classes next to their product class because it’s easy to find them starting from the product class. But doing so, the factories creating body objects by taking in-DTO as parameters would couple the body to the boundary which is bad; the solution is to put them in the boundary model module. However, in practice, I often break this rule (if I’m allowed to) without suffering any bad consequences; still, this doesn’t work if the body is a library used in many projects (which often is not the case).

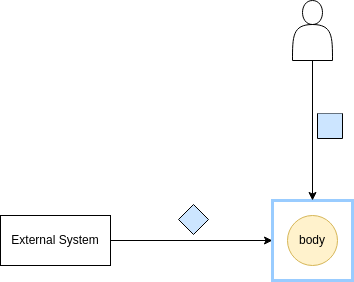

6. The Body

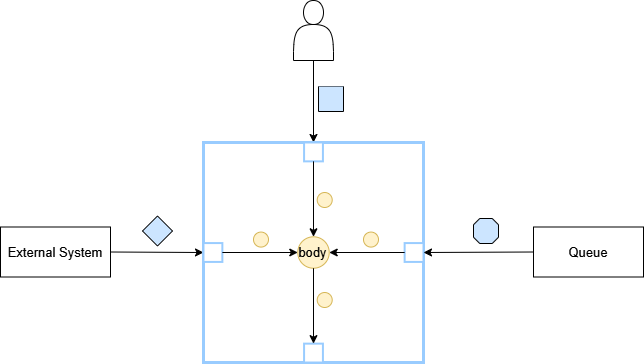

In previous sections, I split an application into boundary and body. One could consider the boundary a set of doors through which messages travel between the external systems and the body. A message might reach the body through e.g. a queue (e.g. RabbitMQ) or a RESTfull endpoint but if the target feature is the same then the message type reaching the body must be the same; the alternative is for the body to “understand” each external system message, which would couple it to them without obtaining any advantage, but only a lot of headaches.

In the above picture, the diamond, square and octagon figures represent the set of message types (aka, “languages”) exchanged between the boundary and the external systems (or user agents). As one can see the boundary is a polyglot, it “talks” all languages the external systems “talk” (e.g. RESTful or RabbitMQ “language”). The body on the other hand is not a polyglot, it “talks” its own “language” and the boundary must understand it! This might not be obvious, especially when using frameworks that automatically convert the external system messages to the body ones. This is fine as long as one doesn’t give up on the temptation of fitting the body “language” into the boundary “languages”.

From a technical point of view, the messages exchanged between the layers (e.g., boundary, body) have the role of DTO; if their type/shape/class differs between the layers, a conversion effort is necessary. Theoretically, there should be a large effort to “translate” the DTOs from one layer to another but in practice, the frameworks do it automatically hence the same DTO could traverse multiple layers.

Technically, all those arrows pointing to the body constitute the use cases list, i.e. what the application can do; however, the business domain might consider a set of them a distinct, single use case. The use cases list is very similar to a book content page hence, easily identifying them is something desirable (I’ll talk more about this in the next section).

7. The Body Modules and Classes

My approach is to create a manager module where I put the Manager classes in charge of the use cases; e.g. PlaylistManager could be a Manager class dealing with audio playlist management. The manager module is the application’s equivalent of a book content page hence, no matter how trivial might be, the Manager class must not be skipped otherwise, it might become difficult to determine what the application does.

I borrowed the name Manager from Martin Fowler’s PEAA book, where a Manager class is the name for an Application Service, and I kept the meaning (i.e., a Manager class is an Application Service). The Manager classes use the adapters (e.g. DAO, message publisher) and the application core (see more about it below) to implement the use cases.

The Manager classes orchestrate the activities performed by the adapters and the core; they won’t do business work but only decide who does what and delegate the job to the appropriate class. The Managers accept requests from the external systems through the external interfaces and use the adapters to accomplish their purpose (e.g. read/store from/into DB, invoke a RESTful service, publish a WebSocket message).

Besides the boundary and managers, the remaining part of the application is the core (more about it later).

In Onion Architecture the core includes these Manager classes plus “my” notion of the core; there, the Manager classes are named Application Services. Application Service is a good name because it nicely contrasts with another type of service, i.e. Domain Services (another ring in Onion Architecture), but I like the term manager for the module name and Manager for the class suffix because they are shorter.

The Manager classes map perfectly to the Use Cases ring from Clean Architecture. “my” core notion maps to the Entities ring though I’m not sure in what proportion; it’s because I’m not totally sure that the Entities layer includes the Domain Services, though I suspect it does, but more about it later.

The messages between the Managers and adapters are usually core objects instead of body ones. However, they could also be DTOs received from the boundary or even from the external systems, if no business processing (i.e., core) is using them; it is the adapter’s responsibility to understand them.

Be aware that DTO is a role; I name core object one used by the core but if passed between layers it’s a DTO too. There are also “pure” DTOs, e.g. a criteria objects used to query some database, which might never reach the core but would go directly through the Manager to the database adapter. In this context, if the Manager is doing nothing else but only to delegate to the adapter, the temptation to skip it is huge. For PoC or small applications, one might give up on this temptation but, if it does so, and some Manager classes are missing from the manager module, later it’ll be hard to tell what the application does – only looking into the manager module (aka, the use cases list) won’t be enough.

Many Managers might use the same input or output message types/classes. In this situation, I create a module named dto or model inside the manager module to keep those types/classes. The dto module should also contain the converter or factory classes that create the core-accepted message types, similar to the boundary dto module; it won’t contain the factory classes that have only core dependencies, those should stay in the core. But as with the boundary model, I again break the rule by putting all core-object factories in the core because I like to have each factory next to its outcome class. Usually, I get away without harm, but, like the boundary model case, if the core is a library, the approach won’t work.

Examples of activities the Manager might orchestrate:

- load an audio playlist from DB (adapter), sort it (core), remove the duplicates (core), then store it back to the DB (adapter)

- check the town hall’s website for new building authorization documents, download them, extract their content, and index them with Lucene (no core activity here)

- accept a payment transaction (Manager method input parameter/message/DTO), load the financial actor profiles from the DB (adapter), compute the fees (core), update the transaction details (core), store them into the DB (adapter)

8. The Core

The core is the part of the application that deals only with the business it is supposed to solve but nothing else. If the business problem is about managing some audio playlist then the core would know only about the concepts/notions/nouns regarding the audio playlist while ignoring the rest, e.g.:

- playlist (it has a name, a location and one playlist-entries object)

- playlist-entries (is a collection of playlist-entry objects)

- playlist-entry (it has a title and a location, e.g. a file path or YouTube identifier)

The core for the above example won’t deal with e.g.:

- persistence

- file system

- presentation

- messaging

- caching

- distributed locking

One might observe that the core is usually small compared to the rest of the application – that’s true, and even Eric Evans points it out in his book (DDD). The core might be overlooked completely if the application is small enough and/or a framework that implements the necessary adapters, is used! For example, if the application is about extracting some data from the database and then sending it through a RESTful endpoint back to the user, then nothing might remain to do in the core if Spring Data REST is used.

On the other hand, if the application is complex the core will contain Entities, Value Objects, and (Domain) Services (see DDD by Eric Evans). The core is composed of the Domain Services layer and Entities layer, the latter containing also the Value Objects.

On behalf of the core I create the model or domain module while inside it I usually create these modules:

- one module for each Entity type (each containing its Value Objects)

- service (contains the Domain Services)

If the parameters or return types of a (Domain) Service operation involve classes other than Entities or Value Objects, those classes can be placed alongside the Service class within a dedicated service sub-module. The commonly used ones could sit into a sub-module of the service module named dto.

The same could happen for the Entities, in which case I create an entity module where I put all Entities; if not many, I put the commonly used Value Objects directly into the entities module otherwise into a vo sub-module of entities.

Let’s visualize a crowded model (or domain) structure:

- model

- entity

- entity1

- …

- entityN

- vo

- service

- service1

- …

- serviceM

- dto

8.1. The Relation with Onion Architecture

The Domain Services and the Domain Model from the Onion Architecture (named so only in part 1) kind of map to what I call the Domain Services and Entities layers (both forming the core). The problem is with the Domain Services layer which, according to Onion Architecture, contains the repository interfaces (see https://jeffreypalermo.com/2008/07/the-onion-architecture-part-1/):

The first layer around the Domain Model is typically where we would find interfaces that provide object saving and retrieving behavior, called repository interfaces. The object saving behavior is not in the application core, however, because it typically involves a database.

From my point of view, the Domain Services layer should contain Services that do what Eric Evans says about them in his book:

When a significant process or transformation in the domain is not a natural responsibility of an ENTITY or VALUE OBJECT, add an operation to the model as a standalone interface declared as a SERVICE. Define the interface in terms of the language of the model and make sure the operation name is part of the UBIQUITOUS LANGUAGE. Make the SERVICE stateless.

It totally makes sense for me that the (Domain) Service’s purpose is to contain the business logic (that’s why the Domain word) that won’t fit an Entity or Value Object. It’s about properly placing that type of business logic but not about interfaces shaping the interaction with some external system (e.g., repository interfaces are shaping the interaction with the DB). For example, if PlaylistEntries is a Value Object containing a collection of file paths, the operation addPlaylistEntries(ple1, …, pleN) that returns a new PlaylistEntries, seems to fit into a PlaylistEntriesService instead of the PlaylistEntries class.

8.2. The Relation with Clean Architecture

The way I define core maps to the Entities layer in Clean Architecture. Although the Entities layer doesn’t explicitly include the (Domain) Services I would say that the author doesn’t exclude them either; here is the Clean Architecture definition for the Entities layer:

Entities encapsulate Enterprise wide business rules. An entity can be an object with methods, or it can be a set of data structures and functions. It doesn’t matter so long as the entities could be used by many different applications in the enterprise.

For me, a Domain Service is the Service Eric Evans talks about in his book (DDD) which seems to fit the Clean Architecture Entities layer. However, I prefer an additional layer, i.e. Domain Services, to differentiate between the (Domain) Services and the Entities layers.

For more about the Domain Services and the difference from Application Services see at least the chapter named Service Layer, sections Kinds of “Business Logic” and Implementation Variations in the Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture by Martin Fowler. Focus on the concept of domain logic compared to the application logic; unfortunately, M. Fowler doesn’t explicitly define the Domain Services, he only talks about the Application Services but combined with Eric Evans’ definition of Service it should be clear that a Domain Services layer sits between the Application Services and the Entities layer. See also the section SERVICES and the Isolated Domain Layer in DDD by Eric Evans, to understand why:

It can be harder to distinguish application SERVICES from domain SERVICES.

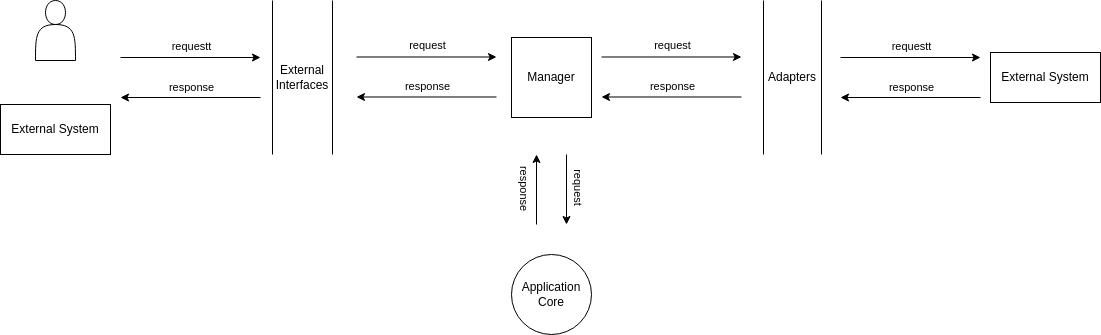

9. The Full Picture

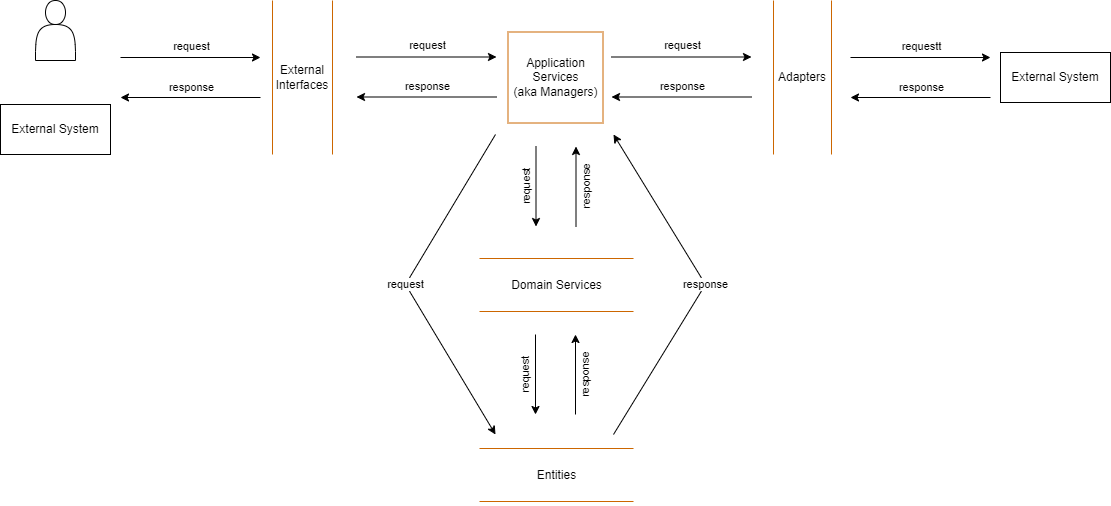

The elements between the colored lines are the layer names; I put the Application Services in a square for graphical reasons only, otherwise, it would be in between two lines too. I point out again that the structure I name core contains the Domain Services and the Entities layers.

I said that I feel the way I view an application design is closer to the Clean Architecture but you might notice that I missed a layer, i.e. Frameworks and Drivers (besides adding Domain Services); from the point of view of the code written by a developer that layer is (almost) non-existent. Usually, the code I see sitting in it is for allocating system resources, e.g. thread pools, database connection pools, and registering objects with the DI (dependency injection) framework. However, in practice this kind of code doesn’t deserve a special module, it can stay in the application root or, part of it, e.g. the DI object registration, in any other module – this last part might feel wrong, especially when thinking of core classes, so check the next example.

Suppose a DI framework is used to create a Manager instance by providing it with various adapter dependencies (e.g. a DAO class). The code to wire the dependencies into the Manager is the “glue code” the Frameworks and Drivers section is talking about. When using e.g. Spring Framework, a common approach is to create a config module where to put @Configuration annotated classes implementing the “glue code” (i.e. @Bean annotated methods). Another approach is to consider the Factory Method and Abstract Factory patterns: the “glue code” creating the Manager is a factory method! For example a @Configuration SomeManagerFactory class could be created and placed next to the SomeManager class; it’ll register the SomeManager instance with the DI as expected while no framework-specific module is necessary. The same could happen for the Domain Services or Entities layer – I think that some annotations (or .NET attributes) on their factory classes won’t hurt their implementation.

TBC